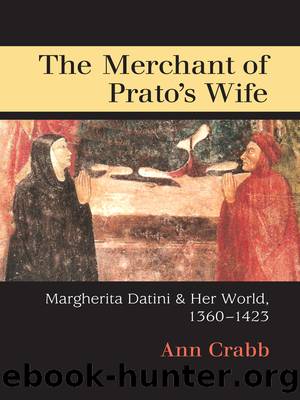

The Merchant of Prato’s Wife: Margherita Datini and Her World, 1360–1423 by Crabb Ann

Author:Crabb, Ann [Crabb, Ann]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Michigan Press

Margherita’s letter to Francesco of 1388 does not seem to have been written for any particular reason. Coming a few months after the birth of his first illegitimate child, it is, however, a little more open about Margherita’s feelings of being neglected and unappreciated than are her other letters. She was staying at the house of her sister Francesca and brother-in-law Niccolò Tecchini, where the only scribe was Niccolò, and perhaps she chose to write herself as best she could rather than confide her feelings to Niccolò. The quality of Margherita’s letter may have suffered from having been written on her lap and with poor implements. Maybe she could have done better under better conditions, but she clearly felt the need to improve.

That Margherita wrote this letter makes it possible that she wrote other letters in the 1380s and early 1390s that have not been preserved because they were not written to Francesco, the preserver of letters. There are a few suggestive comments in letters she sent. In 1384, she enclosed two letters addressed to her mother, Dianora, in a letter to Francesco, asking him to give them to a woman friend who was going to Avignon to transport. “Tell her to take good care of them; I would not have the heart to redo them in a year,” she wrote, perhaps indicating more effort than required for a dictated letter, or perhaps only referring to the delicate phraseology needed for dealing with her difficult mother. In a passage from 1393, Margherita’s brother-in-law Niccolò mentioned to Francesco that Margherita’s sister Francesca could not write (as mentioned above), but the passage included more: “We received . . . the letter Margherita sent Francesca, and since Francesca does not know how to write, it is up to me, Niccolò, to take up the escutcheon and answer for her.” The wording raises the possibility that Niccolò knew Margherita could write or even that Margherita’s letter was autograph; otherwise, it seems gratuitous to mention what would have been well known about Francesca. In a less likely passage, Margherita told Francesco, “This morning . . . I sent you a letter in Stoldo’s hand and two in my hand,” but she was probably referring to “hand” loosely, to describe letters she dictated.12

While the above examples provide possible but unprovable evidence of autograph penmanship, Margherita was working to improve her reading by 1395 and her writing by 1396. She would have been extremely unusual in doing this as an adult woman, since weak skills were normal and accepted for women of the Tuscan urban elite in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries.13 There were a few highly educated women in Italy, so expert at reading and writing that they were specialists in classical humanist studies, but they were the daughters of nobles or of learned men, not members of the mercantile patriciate.14

Not everyone approved of female literacy. Two earlier fourteenth-century moralists who mentioned the subject saw such accomplishments as suitable only for rulers and nuns:

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26603)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23086)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16853)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13337)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7144)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5515)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5095)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4964)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4817)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4802)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4479)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4357)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4274)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4201)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4115)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4033)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3969)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3640)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3467)